For a long time Rafael Nadal was monstrous. Monstrous physically, mentally, tennistically. In his quest for a new Parisian title, the Spaniard was monstrously… human. When he arrived at Roland-Garros, the Mallorcan had never been so weak. Affected by a rare disease in the feet and in total loss of confidence (no title on clay), the player was broken everywhere. The end of Nadal’s reign looked like a slow agony and many specialists thought that the Porte d’Auteuil adventure would be short-lived, especially given the draw. Except that when he enters the Philippe-Chatrier court, Rafael Nadal is no longer the same. He is reborn.

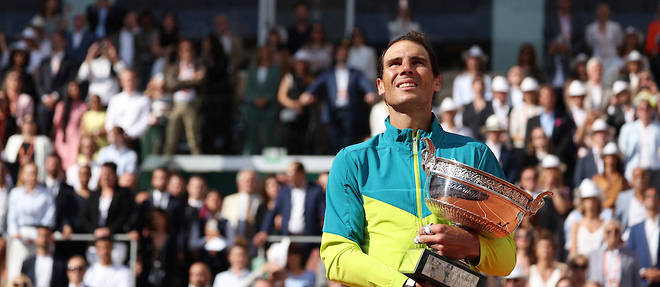

After the first controlled laps, the Spaniard gained momentum and dismissed the applicants who wanted his loss. First Auger-Aliassime, impressive for five sets; then Djokovic in a titanic fight at the end of the night; an extraordinarily cruel battle against Zverev, leaving the court in a wheelchair; and the final victory in three short sets (6-3, 6-3, 6-0) against the Norwegian Casper Ruud. This 14th title, like his triumph at the Australian Open last January, is undoubtedly the most beautiful and the most revealing of what Rafael Nadal has been on the circuit.

The grace and raw talent of Roger Federer has often been contrasted with the strength and selflessness of Nadal. This was true early in his career: he literally destroyed his opponents, returning every ball with more power. But a great champion does not rest on his many laurels. “Doubt is the beginning of wisdom,” prophesied Aristotle. The very wise Nadal knew how to reinvent himself. Throughout his career, the Spaniard has adapted his game. First with small touches (serving, backhand). His monumental defense has not changed, but his palette has been enriched. We started to see Nadal go up to the net a bit. Then some more. During his victory against Novak Djokovic, the Mallorcan went up to the net 30 times where he won 73% of the points – he is also the player who has won the most at the net since the start of the tournament. If we had been told in 2005, when he appeared on the tennis planet with his tank top, his shorts and his baseline game, that he would triumph seventeen years later thanks to his backhand, his serve and his volley , we would never have believed it. This is how he was able to last and export himself beyond his favorite clay court: 22 Grand Slam titles and the second player in the Open era to have won all major tournaments at least twice.

“Rafa” is the praise of work, adaptation and questioning. He fed on the opposition with Federer who also evolved and changed his game. Fourteen years ago, Nadal inflicted a 6/0 on him in the Roland-Garros final. In 2017, at the Australian Open, the Swiss surprised his world by offering a better version of himself. For the first time since 2007, he beat his best enemy in the Grand Slam final. Nadal was inspired by his elder and took advantage of the pressure and power of Novak Djokovic, more powerful, more complete, more “robotic”, to bring changes. What about his eternal returns to the top after his numerous injuries: each time the champion took up the racket stronger than ever. His features pulled, his hair thinned, the cries of pain were louder, but the titles continued to fall into his hands. All with the humility of perfectionists.

In the mid-2000s, you had to choose a side. We were Federer or Nadal. We liked either the beautiful game or the courage. Gentleness or brutality. The topspin forehand volley or end-of-stroke passing. The tics of one, the tocs of the other. If we loved one, we hated the other. The battle over who was the greatest player of all time raged on. In the early 2020s, as this historically unique duo begin to edge closer to release – it’s hard to see how the two could go on any longer, the tennis love is no longer exclusive. It’s one and the other. The proof ? All “Federolâtre” rejoices in the new triumph of Nadal at Roland-Garros. And that he is at the top of the pantheon is not a problem. We love them both – soon all three when the end of “Djoko” approaches, who knows. Because it was them, because it was us.